Incidents of Travel

As part of Moderation(s), the year-long collaboration in 2013 between Witte de With, Rotterdam, and Spring Workshop, Hong Kong, curators-in-residence Latitudes have invited artist Nadim Abbas (Hong Kong, 1980) to develop a public tour of Hong Kong on Saturday, 19 January.

The day-long itinerary plots a course through a handful of sites in the city, which have in one way or another influenced the form, content, and processes of Nadim’s practice. Since Hong Kong has been his home for most of his life, some of these places have been all too familiar to him since childhood. This project now offers him the opportunity to spring fresh surprises on unsuspecting “tourists”, and possibly on himself as well.

To complement the tour, check the Twitter, Facebook and Soundcloud posts via Storify, as well as the text “The Pathology of Hong Kong in the work of artist Nadim Abbas“, an account of the tour by Zoe Li on ArtInfo.com (includes a slideshow).

Follow future events on Twitter: #IncidentsOfTravel #Moderations

Nadim Abbas introduces his tour to 16 participants in the Wah Fu Estate, Aberdeen.

Incidents of Travel: Hong Kong

by Nadim Abbas

19 January 2013

Although I usually speak about my work in terms of images and the imaginary, there is always an equally important component that describes an encounter with external space. By that I am referring to the heterogenous space in which we live, which we rarely have time to reflect upon except in a state of distraction. But just because there is no time to reflect doesn’t mean that these spaces don’t affect our thoughts, subtly penetrating the internal space of our imagination; in some cases to the point where one can no longer distinguish between the internal and the external, or between dream and reality. It is these moments of uncertainty that interest me the most, and which, in my own experience, transforms art making into a perpetual balancing act on the threshold between banality and oblivion.

The itinerary outlined below plots a course through a handful of sites in Hong Kong, which have in one way or another influenced the form, content, and processes that define my practice. Since Hong Kong has been my home for most of my life, some of these places have been all too familiar to me since childhood; waiting for the right opportunity to spring fresh surprises on this unsuspecting tourist.

Wah Kwai Estate block.

Wah Kwai Estate water feature (with no water).

Around the Wah Kwai Estate. Photo: Heman Chong.

Waterfall Bay Park, Aberdeen, Hong Kong

Waterside “resort” used by the local community to swim and exercise by the side of the South China Sea.

Waterfall Bay is said to have attracted Portuguese and British ships to its shores to collect fresh water from its namesake as far back as the 16th century. Today, about 30m from the falls lie the ruins of a WW2 military pillbox and petrol powered searchlight, referred to officially as “Beach Defense Units” by Allied troops during the Japanese siege of Hong Kong in 1941. A few minutes walk from the rocky beach along the coastline, residents of a nearby public housing estate have over the years converted what looks like a disused pier into an veritable seaside resort for the local community. Despite numerous government placards warning against swimming in ungazetted waters, residents eager for an early morning dip in the South China Sea have gone so far as to add ad hoc steps, pool ladders and even fresh water facilities for an after-swim wash.

Tour guide of the day, artist Nadim Abbas.

Photo: Trevor Young.

Looking towards Lamma Island from Waterfall Bay Park.

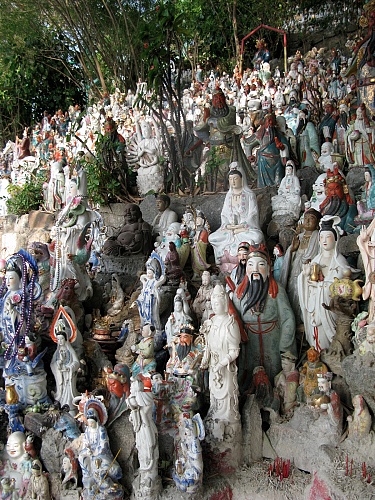

For the less adventurous, there are shelters and seating areas where the elderly gather everyday to play chess/cards, chat or simply watch the boats passing by. But perhaps the most endearing aspect of this site are the hundreds of porcelain statues of various Chinese deities clustered along the hillside and shoreline. I don’t know what started this particular outdoor collection; perhaps a makeshift shrine to protect local fisherman, or to commemorate a traumatic event? Or because it is considered unlucky to throw away statues of deities, they were quietly transferred to this idyllic setting instead. Needless to say, this latter aspect lends the whole site, already steeped in history, with a certain sacred quality. In a city like Hong Kong, where the regulation of land use usually falls into the purview of one dimensional governmental policies or market driven real estate developments, such elaborate appropriations of public space are a rarity. They represent in my mind a kind of fragile heterotopia, or an unwitting piece of relational art par excellence.

Offerings to deities, Waterfall Bay Park, Aberdeen.

Hillside covered with porcelain statues of various Chinese deities.

and more…

…some with their own shelters.

The waterfall of Waterfall Bay Park!

Looking the other direction an abandoned WWII beach-defense unit.

Inside the WWII beach defense unit.

Exploring the bay.

Nadim Abbas, Cataract (Iguazu Falls), 2011. Kinetic lightbox with Duratran print and aluminium window frames. 70(h) x 85(w) x 15(d) cm.

Walking through the Wah Fu Estate in Pok Fu Lam. Photo: Heman Chong.

Wah Fu Estate laundry.

Photo: Trevor Yeung.

Concrete Islands, Eastern Street, Hong Kong

My fascination with marginal spaces in the urban landscape began with this network of concrete islands that are located beneath the Connaught Road West flyovers next to the Western Harbour Tunnel (WHT) entrance. It is a site that I regularly pass by on bus rides to Kowloon side, and it became the model for a 46sq/m sandscape that was built in a warehouse space as part of an installation titled Afternoon in Utopia (2012).

Underneath the Connaught Road West flyover.

Nadim Abbas, Afternoon in Utopia, 2012. Mixed media installation (sand, concrete, pigment prints, painted wall text, red tinted lighting). Dimensions variable (sandscape coverage approx 46 sq/m).

One of the distinguishing characteristics of this particular set of islands are the uniform grids of solid concrete trapezoidal prisms that were set into the ground either by government departments or the government-franchised company that operates the WHT. The usual explanation for this strangely monumental arrangement of blocks is to discourage the homeless population from sleeping on the islands. I see it also as a way for the authorities to mark their territory, much like a dog urinates on a lamppost. A couple of questions remain: are concrete islands private or public spaces? What are the laws and jurisdictions that regulate the use of these spaces? Much like the status of homeless people, it seems that these anomalous zones occupy a certain legal grey area, perpetually overlooked because they exist on the boundaries of function and visibility.

Photo: Heman Chong.

Photo: Heman Chong.

Lunch break at the West Kowloon Waterfront Promenade, site of the West Kowloon Cultural District development, to host the future M+, a museum for visual culture to open in 2017 with a focus on 20th and 21st century art, design, architecture and moving image.

Hong Kong skyline from West Kowloon Waterfront Promenade along the Victoria Harbour.

Man Cheong Street Housing Complex, Jordan, Kowloon

As we all know, Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated cities in the world. This is typically illustrated via descriptions of crowded streets in districts like Causeway Bay, Sham Shui Po and Mong Kok, or of the ubiquitous high-rise public housing estates around the territory. This latter aspect is indicative of the tendency, which began under colonial rule, to build upwards rather than outwards to meet the demands of a growing population. Ackbar Abbas, in Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance (1997) writes: “Hyperdensity is partly the result of limited space, but it is also the result of how this limited space could be exploited for economic gain. On the one hand, the colonial government deals with the problem of hyperdensity by constructing cheap housing estates. On the other hand, the government policy of releasing crown land bit by bit at strategic moments and its prerogative, which it duly exercises, of designating land as rural (where strict building restrictions apply) or urban, ensure that building space remains scarce and property prices remain high.”

Man Cheong Street Housing Complex, a case study in hyperdensity.

Photo: Trevor Yeung.

Stuck in traffic conversations (Left: Mimi Brown and right: Nadim Abbas).

Although the experience of living in a hyperdense milieu is often talked about disparagingly, it has also been argued that the close proximity between the commercial and the residential actually encourages diverse, dynamic communities and a vibrant street culture (in contrast to the the bland homogeneity of suburban sprawl).

In the early 90s, a group of Japanese architects conducted an in depth survey of the city, extolling the virtues of hyperdense living, and going so far as to liken this still existing complex of apartment blocks off Man Cheong Street (another regular sight for me on weekly cross-harbour bus rides) to the infamous (now demolished) Kowloon Walled City: Circulation inside the apparently solid block is not horizontal but vertical. Each slab-building is actually a grouping of towers, separated by slender slots. […] Within these slots of space, like everywhere else in Hong Kong, however, residents have built illegal elements. Thus, although at first glance this highly ordered building complex looks nothing like the chaotic Walled City in Kowloon, it shares with it many features, such as its density of use and its vertical circulation.

Wiring, piping, washing and air-conditioning in the Man Cheong Street Housing Complex.

My own concerns regarding the phenomenon of hyperdensity have to do with the kinds of sub-cultures, or modes of (anti)sociability that emerge as a result of extended inhabitation. This has translated into research and immersion in otaku culture, which carries with it stereotypes of socially inept male subjects walled up alone in their apartments; as if the dense accumulation of cramped interior space encourages an introversion, or vacuum of mental space itself. Interestingly, the Chinese word for otaku is 宅男, where 宅 is short for housing (complex) or tenement (block), and 男 means male.

Nadim Abbas, I Would Prefer Not To (宅男) #9, 2009. Digital C-print photograph, 64 x 42cm.

Shanghai Street, Yau Ma Tei.

The final leg of this tour takes us down a number of well-known streets in Hong Kong, which are prime examples of the kind of vibrant street culture that characterizes a hyperdense city like Hong Kong. They also provide a historical cross section of architectural styles in the region, from pre-WW1 “Verandah” type buildings to modern-day podium towers. Each street is known for its specific cluster of specialized shops and/or stalls. Tung Choi Street, for instance, is affectionately known as “Goldfish Street” since it is almost exclusively lined with pet shops and aquarium suppliers. My choice of these 3 streets in particular reflect my own interests as a consumer as much as producer. In fact it is often the case that I get ideas via shopping, or window shopping – there is always an excuse to pick up another piece of useless junk…

Photo: Heman Chong.

Shanghai Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon

(Kitchen and restaurant supplies)

Meat cleavers and tea pots around Shanghai St.

Pots and pans galore.

Passing by the Kowloon Wholesale Yau Ma Tei Fruit Market.

A durian fruit in the Kowloon Wholesale Fruit Market.

Tung Choi “Goldfish” Street, Prince Edward, Kowloon

(Pet shops, aquarium supplies, bicycle shops)

Goldfish of all size and variety sold at Tung Choi “Goldfish” Street.

Aquarium supplies of all persuasions.

Aquarium supplies to decorate fish-tanks.

Mini red, blue and white lobsters, Tung Choi “Goldfish” Street.

Nadim Abbas, Marine Lover, 2011. Mixed media (Polyresin coral casts, fluorescent black lights, plywood, door frames, mirror), 300(h) x 100(w) x 1900(d) cm.

Ap Liu Street, Shum Shui Po, Kowloon (Electronic components, consumer electronics, camera accessories, hi-fi & AV equipment, hand/power tools & accessories, flea market)

Watches, lighting fixtures, cables, transformers, telephone chargers, wires, batteries, and all kinds of other hardware supplies.

…as well as fishing nets

…all sorts of magnets. Photo: Trevor Yeung.

…and mountains of second-hand drills in the Ap Liu Street market.

1

In his visual essay, On Marginal Spaces: Artefacts of the Mundane (2011), Peter Benz devotes a whole section to the discussion of concrete islands. For a fictional account, see J. G. Ballard’s Concrete Island (1974), a kind of Robinson Crusoe for the twentieth century. 2 See architectural journal, SD (Space Design) Hong Kong: Alternative Metropolis No. 330, March 1992.

– Nadim Abbas (Hong Kong, 1980) is a Hong Kong-based installation artist. His work explores the intricate role that memory-images play in the intersection between mind and matter. This has culminated in the construction of complex set pieces, where objects exist in an ambiguous relationship with their own image, and bodies succumb to the seduction of space.

Abbas studied sculpture (B.A.) at the Chelsea College of Art and Comparative Literature (M.Phil.) at the University of Hong Kong. He currently holds teaching posts at the Hong Kong Art School and City University of Hong Kong. Notable exhibitions and projects include: “No Longer Human”, Osage Kwun Tong, Hong Kong (2012); “Marine Lover”, ARTHK11, Hong Kong (2011); “Cataract”, EXPERIMENTA & Gallery Exit, Hong Kong, “FAX” Para/Site, Hong Kong (both 2010); and “Louis Vuitton: A Passion for Creation – The Hong Kong Seven”, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong (2009).

More info on his work via Saamlung, Hong Kong.

All photos: Latitudes | www.lttds.org (Except noted otherwise in the photo caption)