- Kapnias

There he stood, next to his goats. A disheveled yet not undistinguished figure adorned in the work clothes poor Mediterranean farmers think of as their uniform. His octogenarian weather-beaten face, covered in white stubble, smiled at me. A smile both friendly and ominous, packed with the promise of disturbing tales and indecipherable truths. “We meet at last! Welcome to my poor abode” he wailed, spreading his arms.

I had just driven from Athens to the farm he shared with Yiayia Georgia—his wife—whose life story deserves to be the centerpiece of some talented tragedian’s labor of love. Although Kapnias’ reputation had preceded him, I was not prepared for the quiet ferocity of that night’s welcome. After settling into the bedroom that Yiayia had adoringly prepared, and having broken bread with them, I excused myself and drove to the nearby town to meet with local friends. Upon returning to the farmhouse, well after midnight, Kapnias’ distant snoring and an array of excited cats welcomed me back. Exhausted and ready for a night’s rest in the lap of the Peloponnese countryside, I saw them: Two books resting on my pillow.

One was entitled Memoirs of a Prime Minister. Its author: Adamantios Androutsopoulos, the last ‘Prime Minister’ of the military junta, appointed by Dimitris Ioannidis—the brigadier who took the neo-fascist junta further into neo-Nazi territory after the student massacre of 17 November 1973. The second book was a small leather-bound volume at an advanced state of degeneration. Incredulous even after I read the title, Mein Kampf, I opened it. It was an original edition, published somewhere in Germany in 1934. Bedtime material to shock the visiting ‘leftie’ with, I surmised. Courtesy of a semi-illiterate farmer who clearly wanted to make a point.

Awaking in the morning, I took my time to get out of bed, hoping that Kapnias would have begun tending to his animals and crops in the meantime. To no avail. He was never going to miss my emergence, overflowing with eagerness to gauge my reaction to his late-night offerings. And so we started talking.

Kapnias was an ‘untouchable’ farmhand bonded to Yiayia’s father, who before the war was something of a nobleman in the mountainous village of their origin. A beautiful village that was virtually depopulated later, once the civil war took its toll. During the occupation, Yiayia’s father acted as a liaison between British intelligence and the local left-wing partisans, sabotaging in unison the nearby Wehrmacht brigade and a platoon of Italian soldiers. Yiayia, who must have been the local beauty, fell in love and secretly married George Xenos, one of the partisans. Against the background of a harsh war, two young children were born to the defiantly happy couple.

Meanwhile, Kapnias, the teenage menial, decided to throw his lot in with the other side: He joined a paramilitary unit assembled by the local Gestapo and was sent to Crete for ‘training’ in the arts of ‘interrogation’ and ‘counter-subversion’. It was there that Hans, his instructor, gave him the leather-bound copy of Mein Kampf, like a preacher who hands out copies of the Bible to illiterate natives before moving on to proselytize others.

The war ended but the conflict intensified as Greece sank into the mire of the nightmarish civil war (1944–1949). Allies turned against one another, brother against brother, daughter against father. Xenos, Yiayia’s partisan husband, found himself fighting the national army that was put together by the British and of which her father, given his loyalty to the Brits, was now a local stalwart. Within two years, a modern Greek tragedy had concluded: Xenos was injured in battle and finished off by an American officer during the interrogation that followed his capture.1In 1947 the British, who had been orchestrating the civil war since 1944, so as to destroy the Left’s support base, found it impossible to finance its continuation. So, they passed the baton onto the Americans. Soon after came the Truman Doctrine effectively signaling the beginning of the Cold War and proclaiming that America would draw the proverbial line on the sand, beginning with Greece. Thus, American military advisers, military aircraft, ammunition, and all sorts of support started pouring in. (Indeed, the partisan-held mountains of Greece were the testing ground of the first napalm bomb.) By 1949 the partisans had been destroyed. Yiayia’s father was killed soon after that by partisans for having murdered an injured partisan that sought refuge in his home.2From testimony I have cross-checked, it seems that this was no cold-blooded murder. Yiayia’s father had killed the injured partisan out of intense fear that, if it became known that he tended to him, ultra-right ex-Nazi collaborators might have killed him and his family. Thus Yiayia was suddenly widowed by the nationalists and orphaned by the partisans.

That was Kapnias’s cue. Having made the transition from the Gestapo-organized paramilitary to the local gendarmerie, he was now in a position to exact revenge on the ‘upper class’ of their small world. He approached Yiayia with a simple proposal: “You marry me and I shall stop my ilk from ridding the land of you and your communist seed,” referring to her two young fatherless children. She agreed, hoping that his uniform would provide safety for herself and her children. Alas, soon after, Kapnias was dismissed from the gendarmes for using… excessive force during some interrogation.

Thus a life of poverty, tears, and terror under Kapnias’ domestic tyranny had begun for Yiayia. One that did not abate till her death in 2012.

- The Serpent’s Greek DNA

Nothing prepares a people for authoritarianism better than defeat followed closely by national humiliation and an economic implosion. Germany’s defeat in the Great War and its humiliation due to the Treaty of Versailles, coupled of course with the middle class’ economic implosion a little later, played a well-documented role in the rise of the Nazis.

Greece suffered comparable defeat and humiliation in 1922, at the hands of Kemal Ataturk and as a result of its own government’s hubris.3After the end of the Great War, Eleutherios Venizelos, the pro-British anti-royalist Republican, secured on behalf of Greece the right to administer the Asia Minor coastal city of Smyrna (today’s Ismir). However, soon after the Greek army had taken control of Smyrna, Venizelos’ government collapsed and the new royalist government ordered the Greek army to march on Ankara. This is what gave Kemal Atartuk a great emotional advantage. Countless incensed Turks joined his army and, eventually, Kemal managed to push into the sea the Greek army and proceeded ethnically to ‘cleanse’ millions of ethnic Greeks who had been living in Asia Minor since the time of Homer. In Greece, that defeat, circa 1922, is, to this day, known as the Asia Minor Catastrophe. The political instability that followed, in unison with poverty’s triumphant march after the 1929 global crisis, gave rise to our own variety of fascism: the regime of Ioannis Metaxas that pushed Greece into fascism’s peculiar darkness on 4 August 1936.

Of course, none of this was out of the ordinary. Spain had already fallen into the same crevice. Portugal was similarly afflicted. Italy was in the grasp of Mussolini’s blackshirts. Hungary, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, and the Baltic States all fell to some variant of fascism—its specter was haunting most of Europe before a single shot was fired in 1939.

The question now is: Why has contemporary Greece seen a Nazi revival? Spaniards, the Irish, the Portuguese, the Italians have also felt the ill-effects of the Eurozone crisis in their bones. But why is it that only in Greece has a Nazi party, Golden Dawn, managed to enter parliament in large numbers, while its storm troopers are terrorizing the streets? Kapnias’ story offers useful clues. It throws light on the significance of the Nazis’ attempts to create a local SS-like body of marginalized men disaffected by the local bourgeoisie, by the Left, and living under a permanent cloud of collective disgrace brought on by a previous national humiliation.

In our long conversations, it was abundantly clear that Kapnias remained intoxicated with the power that his Nazi instructors lent him. Alert to his own empowerment from an alliance with the ‘dark side’, he reveled in the departure from decency that was to mark his life thereafter. His very nickname, Kapnias (his real name was George), originated from the Greek word for tobacco [kapnos]; to indicate that he was a bitter, angry man seeking revenge on a world that never gave him a chance. Until, that is, the Gestapo offered him one; a chance that he grabbed with both hands and was savoring to the bitter end. Surrounded by his unsuspecting goats.

“The Germans were above God,” he told me. “Unlike the Italians or our own mob, they could use any means to get the job done. Without wincing. With no fear. No passion.” “You had to see them with your own eyes.” “They were magnificent,” was his last utterance on the matter, his face lit up like a Christmas tree, his heart filled with extra pleasure from noticing that my stomach was turning with every one of his words. Still, I felt I understood where he was coming from.

Being handed that little leather-bound book, which Kapnias did not have the German to read, was like an induction into a European Brotherhood of Evil; the type of evil that, when shared with a force so much more technologically advanced in relation to their own community, gives marginalized, cowardly men, like Kapnias, a priceless sense of belonging to some Circle of the Select. A sense that can elicit a hideous outpouring of violent sentiments, words, acts.

Kapnias died in 2009. Tragically, the serpent’s DNA did not perish with him. His generation did not fade away after the left-wing partisans were crushed in 1949. They remained central to the post-war state, murdering left-wing MP Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963, and even taking power in 1967, thus immersing Greece in yet another bout of neo-fascist totalitarianism. And when the Athens Polytechnic students’ uprising shook their regime in November 1973, it was a true-blue Nazi, brigadier Dimitris Ioannidis, who pushed the fascist colonels aside and imposed the darkest post-war hour upon the nation.

After the junta’s collapse in 1974, the serpent recoiled in its lair. I recall spotting single copies of the weekly newspaper 4th of August (referring to Metaxas’ 1936 fascist coup) hanging in my neighborhood kiosk. It seemed to me that no one bought a copy. Unable to resist the temptation, I bought a copy once myself! It was my youth’s equivalent to watching a horror movie and enjoying it against my better judgment.

While in 1974 the fascists had gone to ground, following the generalized outpouring of anti-junta, anti-fascist emotion, it was not too long before the ultra-right started rearing its ugly head again. In the 1977 general election a far-right umbrella party, under which royalists, junta loyalists, fascists, and Nazis congregated, scored a respectable eight percent of the national vote. A year later, in 1978, a certain Mr. Nikos Mihaloliakos, Golden Dawn’s current führer and parliamentary leader, was arrested for bombing two cinemas. Upon his early release he began publishing a weekly. Its title? Golden Dawn.

Throughout the 1980s, various ultra-right organizations came and went, with fascists and Nazis jostling for position within them. They were never anything other than marginal organizations that had no chance of scoring the vote share that would have propelled them into parliament. Nevertheless, the Serpent’s DNA was preserved inside these groups, ready to sprout a myriad of snakes when the conditions permitted. In February 1983, Nazi thugs viciously attacked Yannis Evangelopoulos, an eighteen-year-old boy, the son of former partisans and civil war refugees who had recently returned to Greece from the Soviet Union. It triggered a number of attacks, one of which was caught on camera, featuring an ax-wielding student leader who is now a Conservative Party government minister. Nazi brutality was on its way back.

- From the 2004 Olympics to the 2010 Memorandum

If Greece managed to enter the Eurozone it is largely due to the influx of migrant labor in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Iron Curtain. It was this torrent of undocumented workers that pushed unit labor costs down and allowed the European Union to get away with the pretence that the Greek economy might just stand its ground in Europe’s ill-conceived monetary union. Moreover, from 1996 to 2004, Athens had been turned into a worksite, preparing as it was for the 2004 Olympics Extravaganza.

While the country was abuzz with the sound of bulldozers and drills, the earlier gigantic struggle to get the country into the Eurozone had condemned a large segment of poorer Greeks into a slow-burning, unseen recession. Wages were rising just above the official rate of inflation but the prices that the poor paid for the goods that they purchased were rising much faster. Thus a gap emerged between the native working class and new, undocumented migrants, who were content to work wherever and at all hours so as to put money aside to send back home or to save for a brighter future.

While the stadia, the railways, and the motorways were being built, a certain tranquility seemed to hold. Yet, the writing had been on the wall from at least 2000 when an ultra-right-wing party, LAOS, made an impromptu appearance, managing to bring together nationalists, fascists, and Nazis under the leadership of a self-serving, personable, vegetarian, low-brow television journalist, Mr. George Karatzaferis. Soon, the new party, riding on a wave of support from working-class natives that felt threatened by Greece’s new economic realities in general, and by migrants in particular, scored some early electoral success. By the time of the 2004 Olympics, they had a sizeable parliamentary presence.

In the summer of 2004, as the Olympics drew closer, migrants who used to labor like the proverbial ants, getting the stadia ready in time for the athletes and dignitaries, suddenly had no jobs. They became more visible and less moneyed. It was at around that time that the Nazi elements within LAOS shifted into high gear, planning a campaign of ‘cleansing’ in neighborhoods such as Aghios Panteleimon near central Athens. LAOS was split between fascist nationalists under its leader that were eager to enter the political mainstream and be seen as potential members of a governing coalition, and Nazis who coalesced under Mihaloliakos and the Golden Dawn imprint. Copying the strategy first pioneered by the German ultra-right NPD party in Eastern Germany in the 1990s, Golden Dawn aimed at ‘liberating’ suburbs in which many of the migrants lived. They called them “brown scum” and soon set up ‘citizens’ committees’ along the lines of supremacist vigilante groups, tolerated (and in many cases aided) by the local police.

Before too long, certain areas, like Attiki Square (not far from Athens’ city center), became hunting grounds for anyone that looked ‘different’. Migrant-owned shops were targeted Kristallnacht-style on many, many different nights and the victims learned the hard way that it was meaningless to take the matter to the police. Even ‘legitimate’ television stations gave a platform to the ‘incensed locals’ who went live with descriptions of migrants as rabies-infected animals that had to be put down. Interestingly, the dominant narrative soon began to include in the list of those who ‘have it coming’ prostitutes, gays, lesbians, ‘left-wing migrant-lovers’, and, of course, transgender people.

In addition to the local circumstances, there were two other factors contributing to the inexorable dynamic which conjured up the tide that lifted Golden Dawn from a minuscule hideous gang to an evil force to be reckoned with. One was the Conservative government (2004–2008) that was keen to play to the xenophobic gallery for electoral gains. The other was real estate developers for whom the Golden Dawn represented a chance in a million to make a nice little earner—to buy properties at low prices, have the migrant ‘scum’ removed forcibly by Golden Dawn, and then cash in.

Then came the economic tsunami that bankrupted Greece in early 2010 and led to the infamous Memorandum of Understanding with the troika (comprising the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund). A loan agreement, with strings attached, that demolished Greece’s social economy from 2010 onward. In contrast to the other southern Eurozone countries also sporting a history of fascism (i.e., Spain, Portugal, and Italy), the Euro Crisis brought a reduction in Greece’s national income ten to fifteen times greater than elsewhere. Throw into this mix the Kapnias story (which highlights the importance of the Nazi presence in Greece in the 1940s at a time of fierce resistance by Greek partisans to their occupation), and you may begin, dear reader, to converge to an explanation of why Nazism re-appeared in Greece and not elsewhere in Europe’s periphery.

- Nazis in Power, Even Though not in Government

In November 2011 the socialist PASOK government of Mr. George Papandrou, which had acquiesced fully and almost enthusiastically to the Memorandum of Understanding that most Greeks associated with their personal and national catastrophe, collapsed. From its ashes their rose a tri-party coalition government comprising PASOK, the conservative New Democracy and LAOS, whose leader saw this as an opportunity to place his ultra right-wing, fascist grouping in the political mainstream.

Alas, the result of this historical compromise was a split in LAOS. Some of the more enterprising fascists joined New Democracy, which could reward their ‘apostasy’ with better ministerial positions and a safer political future, while the Golden Dawn grouping went their own way. Within months, opinion polls showed that the Nazi Golden Dawn had overtaken the fascistic LAOS. By the time of the next election, in May 2012, Golden Dawn was in parliament and LAOS had to all intents and purposes disbanded.

Fully cognizant of the shock value of the following statement, I shall assert that Golden Dawn got its first taste of real power just before the May 2012 election—even before it stood for office. It came in the form of a despicable decree issued by the then minister of public order, Mr. Mihalis Chrysohoidis, a longtime PASOK minister who had made a name for himself because, under his political leadership, the police had managed, after decades of trying, to capture the members of Europe’s most ‘successful’ left-wing terrorist organization—the so-called 17 November group.

Chrysohoidis decreed that the police should arrest prostitutes in central Athens, most of whom were of course undocumented migrants, forcefully subject them to HIV tests, and have their photographs and names posted on the ministry’s website so as to… supposedly warn their clients. Over several weeks, police would sweep Athens arresting, with no warrant, any woman that did not seem ‘respectable’, shove her in a van, and take her to the police station where officers would restrain her while nurses extracted blood. And if the test came back positive, they would throw her into a police cell without any counseling whatsoever.

In one fell swoop a multitude of a liberal democracy’s cherished principles were torn asunder: the principle that the state does not have the right to subject individuals to medical tests without their consent; the principle that public health is jeopardized when potential HIV carriers do not trust medical personnel and the authorities to respect their basic human rights; and the principle that ‘clients’ and sex workers have a duty to themselves and to others to always use a condom on the assumption that the sex worker or the client may be infected.

All these crucial principles were thrown into the dustbin overnight. For what? So that two embattled PASOK politicians, Mr. Chrisohoidis and his mate in the Ministry of Health, a Mr. Andreas Loverdos, could entice some racist bigots to vote for them, rather than for Golden Dawn, in the forthcoming election.

It is in this sense that I am making the claim that Golden Dawn found itself in power even if it never entered the government. For why should its thugs care about governing if their policies are enacted by the ‘legitimate’, yet powerless, political forces in government?

As if to confirm this claim, the government that was installed after the two consecutive elections of May and June of 2012, passed a remarkable piece of legislation through parliament. One that wrote into the statutes that Greek citizenship and good grades in university entrance examinations were not sufficient for a young person to enter the police or the military academy. What else was needed? Proof of ‘ithageneia’; that is, of a Greek blood lineage that naturalized migrants were, naturally, denied. Why do this? To play to the Golden Dawn voters, who like all Nazis have a penchant for ‘blood and land’, in the hope of enticing them back into the fold of the ‘civilized’ parties.

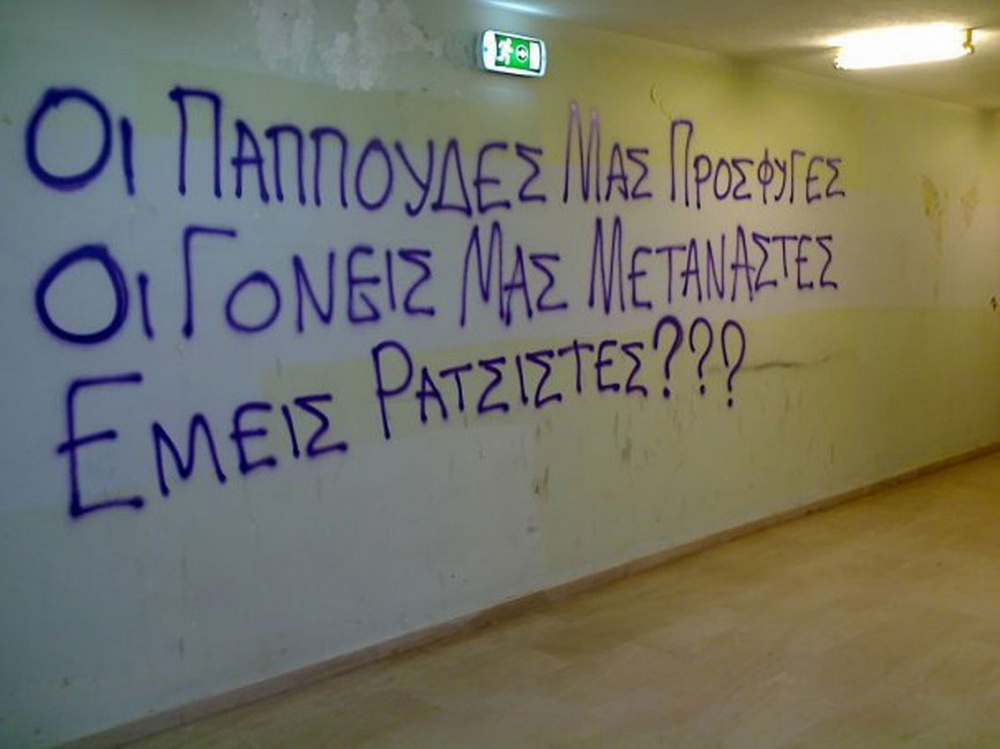

Thus, for the first time since the Nazi laws of the 1930s, a European country introduced legislation that segregated its citizens (and not just its residents) between those that are Greeks-by-blood and those who are not. As I am writing these lines, a vile chill travels fast through my spine. And a deep shame fills my heart and mind. Shame in being Greek and, also, shame in being European, since Europe seems to have brushed such an abomination aside.

- Pavlos’ Game-changing Murder

By the summer of 2013, dozens of migrants had been kicked, stabbed, and beaten to a pulp by Golden Dawn thugs, while the police turned a blind eye and the governing coalition struggled to make political capital out of them by peddling the ‘two-extremes theory’: painting SYRIZA (Greece’s official opposition, and second-largest party in parliament) as “the other side of the Golden Dawn coin.”

In mid-September, with the economic crisis worsening despite the governmental proclamations of a Greek Success Story, the pro-government media toyed with the idea of a New Democracy-Golden Dawn accommodation. For instance, the chief economics correspondent of the influential SKAI TV and Kathimerini newspaper, Mr. Babis Papadimitriou, made an extraordinary statement live on air. In a discussion with a member of SYRIZA, he asked: “If your party is thinking of seeking a vote of confidence from the Communist Party, why should Mr. Samaras’ New Democracy not seek the support of a serious Golden Dawn?”

A ‘serious’ Golden Dawn? While Mr. Papadimitriou, with whom I have debated live on SKAI TV numerous times, was clearly repeating the mantra of the present coalition government (namely that Golden Dawn and SYRIZA are the different faces of extremism), he and his ilk in other news media making a similar suggestion seem unwittingly to have caused a backlash within Golden Dawn. As Golden Dawn officials stated on their website, they refuse, point-blank, to get ‘serious’; to be co-opted by the conservative New Democracy. While clearly happy to play the role of SYRIZA’s deadly foes, they are not going to taint their ‘Nazi purism’ with any notion of lending their parliamentary votes to New Democracy.

Pavlos Physsas’ horrendous murder on 18 September 2013 served, partially, as a signal of the Golden Dawn’s determination not to be co-opted by New Democracy. Pavlos was, as many around Europe have heard by now, an anti-racist rapper of astonishing virtue and courage. Dedicated to the peaceful struggle against Golden Dawn in the working-class suburb of Keratsini, he posthumously forced Greek society to acknowledge that the serpent’s egg had not only hatched but that it had produced venomous snakes intent on taking a terrible toll. No longer content to bash migrants and to intimidate their opponents, the Golden Dawn thugs had calculatingly adopted a new tactic: Unleashing deadly violence against left-wing activists—first against a group of nine Communist Party members, whom they hospitalized, and soon after with Pavlos’ deliberate murder.

Berlin was incensed. I have it on good authority that the Greek prime minister received urgent calls suggesting to him, in no uncertain terms, that Golden Dawn could not, and should not, be tolerated. Golden Dawn’s hierarchy had to be taken out, for otherwise the European Union’s fiscal consolidation program in Greece would be associated with the unchecked rise of a murderous Nazi gang. The prime minister’s problem was that the Golden Dawn’s leaders are members of parliament and, as such, they enjoy immunity from prosecution. The only way that they could be arrested is if parliament convened and voted for a suspension of their immunity.

While such a vote would be carried without a shadow of a doubt, and with a crushing majority, there was a snag: The prime minister feared that a number of his own members would abstain or even vote against, revealing to the whole world the extent to which Golden Dawn’s ideas had purchase within his party. For this reason his government took a different approach: Invoking an article in the Greek constitution that enables the authorities to arrest, without exception, members of a criminal organization, the government and the judiciary ordered the indictment, and arrest, of Führer Mihaloliakos and his deputies for having formed a criminal organization.

The problem with this tactic is that it stands a great chance of backfiring. For it is now incumbent upon the state prosecutor to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Golden Dawn, an organization that was formed in 1978 (and formally constituted as a political party in 1987), was formed back then for the explicit purpose of carrying out criminal activities.

My great fear is that either the prosecutor will fail or that he will succeed by concocting evidence in support of this particular, exceptionally narrow, charge. Either way, the Nazis will have scored another victory against a democratic order that will either have to release them, to the triumphant chanting of their blackshirt supporters, or imprison them by bending its own rules of judicial propriety.

- Epilogue

My encounter with Kapnias taught me much that is relevant today.

It taught me that our loathing of Nazis reinforces their commitment and renews their spirit.

It taught me that only the resistance of unassuming, hate-free heroes like the fallen Pavlos Fyssas can destabilize them.

It taught me how a Greek who had never encountered a Jew, or nowadays a Pakistani, could be programmed to believe that therein lies the cause of all his suffering.

It taught me that the serpent dies hard. That putting its minders in jail does nothing to eradicate it. That once it is implanted into a society forced to surrender unconditionally, as Hans had done with his leather-bound gift of Mein Kampf to Kapnias, its DNA lurks—even if the serpent is actually killed.

And it taught me that: When proud nations, which were previously implanted with the serpent’s DNA, are beaten into submission within our Euro-Jurassic Park, when they are humiliated and punished collectively, as the Germans were with the Treaty of Versailles, and the Greeks under our current bailout conditions, and when they are reduced en masse to a state of despair, the serpent can always return, replicate ferociously, and run amok.