It is 42°C (108°F) this weekend, and even the Athenians are concerned. The newspapers are calling it a heat wave and those who have not escaped to the islands or the mountains—the traditional Greek exodus in the summer months—are mostly in hiding. The city has installed more than forty special water tanks across the city for stray animals, while the General Secretariat for Civil Protection has ordered the extended opening of Friendship Clubs for the over-50s: air-conditioned rooms where older people can get some respite from the heat. The night brings little relief, with temperatures still hovering in the mid-30s (95°F). The optimal temperature for sleep, according to medical research, is a cool 18° (65°F), and the result of torrid nights is restlessness and strange dreams. In Athens, the high nocturnal temperatures are combined with a full moon, which peaks this week on the same night as the summer solstice, giving pretty much everybody one reason or another for sweaty fitfulness.

Sleep seems to be on the Athenian mind this summer. The Hypnos Project—from the Greek word “Ὕπνος” [sleep], which gave the English “hypnosis”—has just finished a two-month program at various venues around the city, which included sleepovers, scientific experiments, and Freudian theory lectures alongside an exhibition of artworks related to sleep. The dark and labyrinthine exhibition space in the basement of the Onassis Cultural Centre gently sedated entering visitors with Orestes Davias’s Plantae Epimenidae (2016), a cabinet filled with hypnotic herbs and draughts, including poppies, valerian, mandrake, and chamomile, before proceeding to distress them: Dimitris Xonoglou’s Bed (1996) offered the viewer a wooden bed crushed by a fallen chandelier while Thanassis Totsikas’s He fell asleep in his dream (2016) presented a sleeping head surrounded by sharp knives. Even the inclusion of paintings from Greek masters, works such as Georgios Iakovidis’s dozing Refugee Girl from 1905—an exhausted, poverty-stricken child—and Théodore Ralli’s shadowy Odalisque of 1885—that most troublesome of Orientalist figures—mostly served to disturb rather than soothe.

Sleep, like everything else in Greek life right now, is of course political. In tune with the temperatures, Hypnos Project curator Yorgos Tzirtzilakis said in an interview that sleep is an “overheated factory.” His colleague Theophilus Tramboulis, elaborated: “We think that sleep begins where civilization ends. That when we sleep there is no place for society, the economy, politics. We fall asleep and we forget everything, we retreat and only when we wake up does public life once more begin, the suffering of the body and of work. But it is not so.”1Beetroot in conversation with Hypnos Project exhibition curators, “Hypnos Project. A User’s Guide,” Analyze Greece (13 June 2016), http://www.analyzegreece.com/topics/culture-in-time-of-crisis/item/444-hypnos-project-a-user-s-guide (accessed 19 July 2016).

Nowhere was this clearer than in the final installation in the Onassis basement: a full-size reconstruction of a torture cell. During the rule of the Colonels from 1967 to 1974, the Greek Military Police and the Special Interrogation Unit perfected the use of sound to prevent sleep and induce stress, anxiety, panic, and pain in detainees. As documented in the torturers’ trials of the late 1970s, the regime used motorcycle engines, gongs, metal drums, and electric bells in the prisons of Athens and Piraeus, while on the prison islands of Makronisos and Gyaros the Junta’s “re-educationalists” blasted folk music from loudspeakers at all times of day, both to instill patriotic feeling and to assert their supposed nationalist legitimacy. In a sheet-steel corridor, the researchers Anna Papaeti and Nektarios Pappas recreated the intense and physical effect of continuous noise on the visitor, while testimony from the torture victims was relayed through headphones outside.

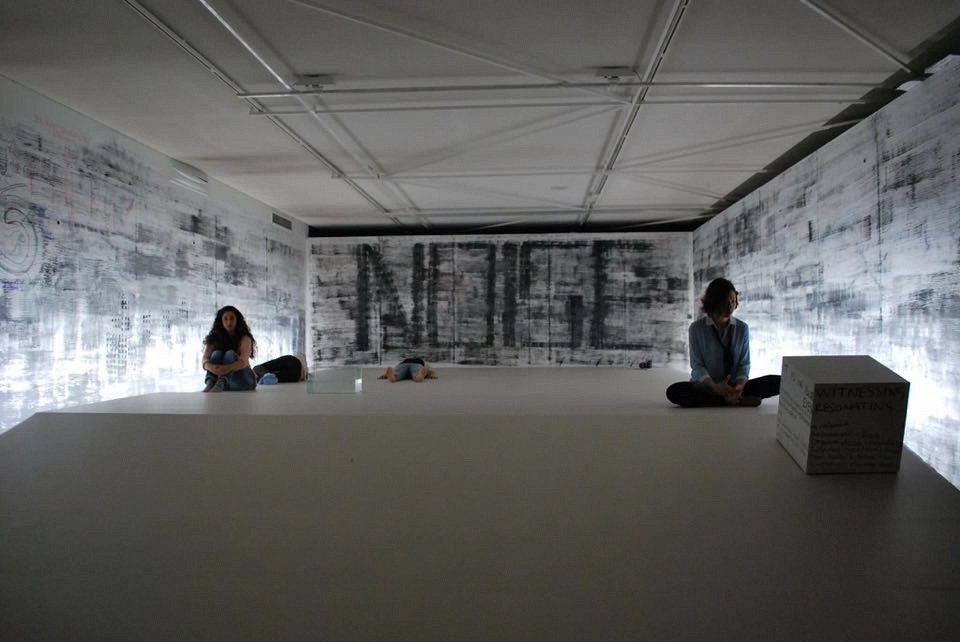

Papaeti and Pappas’s installation formed a strange twin with Lambros Pigounis’s Micropolitics of Noise (2016), another work recently on view across town at the Benaki Museum’s Pireos St Annexe as part of Marina Abramović’s “As One,” a series of durational performance pieces by Greek artists presented alongside Abramović’s own “method.” For seven weeks, eight hours a day, Pigounis exposed himself to subsonic vibrations atop a wooden platform in a near-soundproofed space. Scrawled on the walls around him was his record of the experience: diagrams of the body, dated accounts of psychological effects, and echoes of research into not only the Junta’s use of sound and sleep deprivation, but its latter deployment in Northern Ireland, Iraq, Guantanamo Bay, and elsewhere. When I visited, the artist stood frozen and staring, his body taut, atop the platform, showing no sign of human recognition or awareness of the audience. For weeks after leaving him, I kept thinking back to the experience—his ongoing experience—in that room. While both pieces reflected upon the intense effect of sound and sleeplessness on the human body, Pigounis’s presentation in a white-walled contemporary art space rather than the set dressing of the Onassis basement seemed to emphasize the everyday effects of continuous stress. In his artist’s statement, he wrote: “The social, physical and psychological affects of sound as a form of violence remind us that conscious emotion is unnecessary in producing fear responses.” Indeed, most of what affects us emotionally today, or is learned from the measuring of those emotions, takes place in intangible and invisible, unconscious space.

The monitoring and control of sleep is no longer the preserve of authoritarian regimes, but simply part of the wider power of networks, corporations, and governments. From e-mail and calendars shared and stored “in the cloud,” an increasing volume of data is devoted to health monitoring. Apple’s Health app, first announced in 2014, allows users to track their physical activity, diet, heart rate, blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol, and many other data points, while its developer counterpart HealthKit allows other manufacturers to add to and do stuff with that data. Soon, Apple hopes, it will also be able to read their medical records. Many of the most popular Healthkit apps are also sleep trackers. A typical example, Sleep Cycle, requires users to place their phone on the nightstand and point the microphone toward them before settling down, or even to place the phone under the bedsheets to better gauge restless movements through the device’s accelerometer.

In his polemic 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (2014), Jonathan Crary argues that sleep was the last frontier of control, the last terrain to be subsumed and capitalized—and one which is rapidly being given away of our own volition. I cannot think of a more powerful image of what Crary terms the “compliant subject who submits to all manner of biometric and surveillance intrusion” than the iPhone user, curled around their handset even when sleeping, silently and endlessly transmitting their data to the cloud.2Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London and New York: Verso, 2014).

But perhaps the strangest and ultimately most unsettling story that I have heard recently about sleep and sleeplessness concerns just such unconscious fears. For one of the public events associated with the Hypnos Project—and one which was quickly fully booked—participants were invited to spend the night being monitored by the technicians of the Evangelismos Hospital Sleep Disorders Center. The pioneering center was established in Athens in 1990, but similar clinics have proliferated in recent years, as once-rare disorders such as sleep apnea (when a sleeper momentarily stops breathing, causing disturbed or interrupted sleep) appear to be on the rise in the general population. By 2014, Evangelismos was hosting 9,000 people per year for overnight stays. The rise is attributed to many factors, including increasing obesity and the use of mobile phones and laptops in bed, and it also has economic repercussions. According to research by the newspaper To Vima, Greek sufferers have been particularly badly hit during the crisis, as pension funds have cut the amount they are willing to shell out for medical equipment, refusing to cover treatment options such as positive airway pressure (PAP) devices, which typically retail for over €1,500. As the economic and political situation fails to improve, it is hardly a surprise that such devices are in ever greater demand among the fretful sleepers of Greece.

Devices like PAPs are typically recommended for sleep apnea sufferers after they have been evaluated at a sleep clinic, just as the visitors from Hypnos were assessed. The process typically involves a type of sleep study called polysomnography, where the patient’s brain waves, oxygen levels, heart rate, and breathing are monitored through the night, as well as eye and body movements and any sounds the patient makes. All of this information is captured by diagnostic machines that store patient data alongside their medical profiles. Increasingly, such machines are also connected to the Internet, in order to ensure that they are being correctly used (France, for example, requires hospital diagnostics machines to be connected to a monitoring network), and to share diagnostic data with the manufacturer.

And where does all this data go? As we have seen, it is not merely the devices in our pockets that are sharing secrets with distant servers, but our doctors, nurses, and the machines in the sleep clinics. These machines are required by contract and by law to be permanently connected, wired by Ethernet cable to the telephone system, or communicating through internal, encrypted SIM cards with a mobile network. While we doze, every toss and turn, each kick of the leg and sweaty grunt, the rhythm of our snoring and the mumbling in our sleep—the very texture of our stressed and fractured slumber—are being stored in distant, vast, and anonymous corporate data repositories: warehouses of dreams, awaiting some future oneirocritic of Europe.