I remember my finger cresting the left downward line of the V in Van Bemmelen, carved into a tombstone, my palm flat on the granite and the ball of my sneaker on grass. The road was dirt with ruts and potholes. Motorbike lights filled them. Then there was a roundabout with a giant weeping tree in it. The horizon was all city lights blowing upward. In the center of the graveyard it was dark and there were stars. We pushed a little further than we might have been comfortable with otherwise. Feeling a little guilty but also knowing that it will always be like that, when you have not seen someone in a long time and you are tipsy. But more than that: this is what desire does, it follows crevasses.

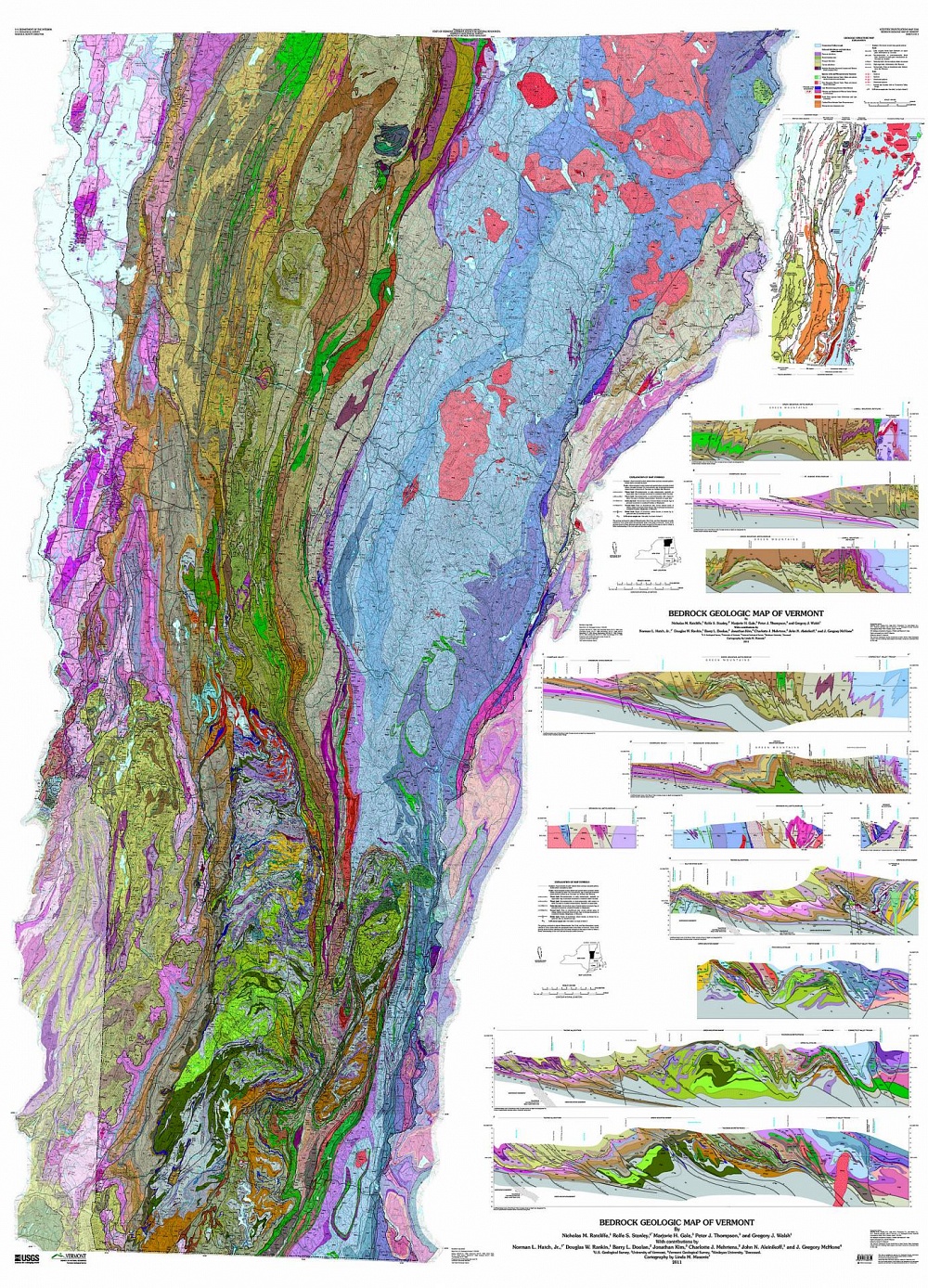

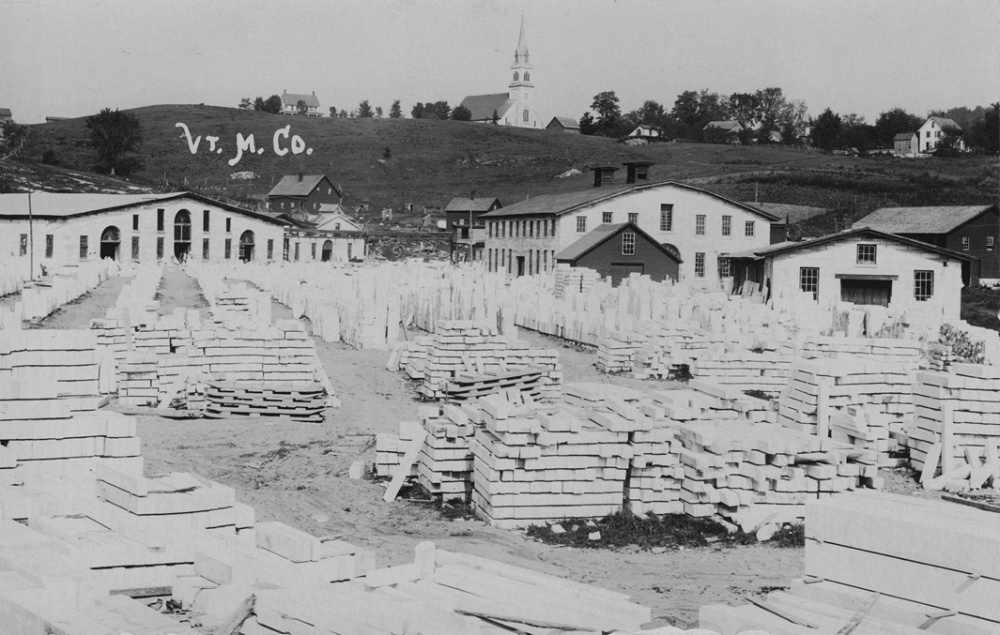

I'm in Barre (pronounced like “hairy”), Vermont. About 400 million years ago when there was very little land and it was all crowded around the south of the globe, a magma globule ejected from the core of the earth. Rising through the mantle, it crystalized. The mass it was embedded in smashed into others, intercalated its finger shaped form with others. Its frayed edges rolled like dough around adjacent masses. The continents were ripping apart, gliding along the currents of the mantle. They floated into a form that came to have our contemporary names: Asia, America. Vermont. The globule was called a pluton, a solid mass the size of a few bundled skyscrapers with a tip protruding from the surface.1The globule is granite, and the small settlement adjacent to Barre built on the vein is called Graniteville. Granite, according to Charles Lyell, is: “An unstratified or igneous rock, generally found inferior to or associated with the oldest of the stratified rocks, and sometimes penetrating them in the form of dikes and veins. It is composed of three simple minerals, felspar, quartz, and mica, and derives its name from having a coarse granular structure; granum, Latin for grain. Westminster, Waterloo, and London bridges, and the paving-stones in the carriage-way of the London streets are good examples of the most common varieties of granite.” Charles Lyell from Principles of Geology (1830–33). The geological history of Vermont’s industrial minerals can be found here: http://www.anr.state.vt.us/dec/geo/graniteindustry.htm (accessed 24 February 2015). A town grew around it, hacking at it slowly to make monuments, carving war heroes on pedestals. On their necks were wrought garlands and their jackets made to crease around their elbows. They also made blank headstones that they distributed around the country to be engraved and individualized with names like Stevens, Levesque, Klein.

We need a new geocartography of the body which situates the body in geological processes.

Milk is bone made for distribution. Teeth are rock formations in the mouth.

One preoccupation of nineteenth-century empirical sciences was the relation between the immediacy of our desiring bodies and the deep time of the geological. You can see this being worked out in the debates and controversies between different scientific practices but it is also internal to the work of particular figures who grappled with the distinction between the organic and the inorganic, two excellent examples being Humboldt and Darwin. How did our soft bodies, full of wants, pleasures, and pain, living for short periods, have anything to do with the time it took to form Everest? Our organic natures were defined in difference, a gaping difference. We came to be considered a species caught up in the open-ended experiment of animals and plants roving across an inorganic landscape like it was a theater set. The inorganic was what we encountered as a terrible indifference to our flesh.

Since dissociating the inorganic from the organic we have been scrambling to put them back together. The nineteenth century was fixated with matter animated. Bergson imagined the inert material of the world to be suffused with an élan vital which came from outside but gave the world life: motion, force, yearning. Matter formed the conditions for life to begin its project. “Precisely how life began is still a mystery…” Says one contemporary biology textbook.2“Precisely how life began is still a mystery, particularly since the prevailing conditions of early Earth were inimical to life as we know it today. The embryonic Earth was a protoplanet devoid of atmosphere, cracked by volcanic upheaval and lightning, flooded by a lethal ultraviolet light, and rained on by the rocky debris of a juvenile solar system still actively in the process of birth—a world whose original surface was molten rock and whose first atmosphere, largely composed of hot hydrogen gas, was vented into space almost as quickly as it emerged from the Earth’s radio-active core. Although hard to conceive of, these were the conditions when Earth formed roughly 4.6 billion years ago.” The paleobotanist Karl J. Niklas, with marvelous synthetic powers, rests his history of “living things that thrive without intention, build without blood or brain, move without muscle, summon without self-awareness, and feed the world without intent. In short… plants” on the foundational distinction between the non-living (inorganic) and the living (organic). However, even in this first paragraph he points to the human as a being between two registers: “Astronomers like to say we are fashioned from stardust—that the elements in us were formed in ancient, long vanished stars and differ not at all from those found in the outer reaches of space. If so, then it is also true that we are made from starlight—that our substance is predicated on the way plants convert the energy of sunlight into chemical energy.” Karl J. Niklas, The Evolutionary Biology of Plants (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1997). This is still no different from the nineteenth century: at some point before, life was not. We are still Victorians when we go to outer space looking for life as if it were not already everywhere, or everywhere suffused in it.

It has become such a significant distinction that we use it to identify the living from the dead. And we know how easy it becomes to arrange privileged forms of existence and despise that which does not partake of life. This innocent distinction comes to pervade our conception of what it means to live together and in the world: those and that which does not fully partake of life can be killed, mined, exploited. What would the world look like if there were not such a distinction?

Would thinking otherwise forge a thought that thought mouths and rocks at the same time? Would a post-organic/inorganic division bring us a different theory of orality from Freud, who relied on the distinction between the organic and inorganic in his theory of desire? For him, desire is an extra geological force, it is what jumps the line from the dead to the living; a force that compels, wants, seeks, sets matter in motion. The mouth is a substitute for other biological assemblages and contraptions of desire: anuses and vaginas. In the alternative, an animate geology, the orifice of the mouth is an entanglement between the rhythms of calcification, the flows of salivation, and the articulations of muscle. To look into a mouth is to look across a limestone ridge. To chew, a collaboration with topography.

Would this be a renewed thought of soil, against the twentieth-century’s misconception that it is the substrate of culture, its attempt to harness soil for the project of the nation, and for its mistake that the soil is a space of belonging? Instead, soil is between life and death. It is earth becoming biota. The surface of the earth is the entanglement of life and non-life, their indistinguishability. There, our tough distinctions begin to fall apart. Dirt grows. Plants ingest and internalize the earth, its crust, which is its mantle, which is its core. Edaphologists are, etymologically, those “who speak the ground” (“edaphos” + “logos”). They traffic in this heterogeneous world.

My flat palm on a tombstone with a finger cresting the V was in Surabaya (East Java) in the Kembang Kuning, a graveyard adjacent to a red-light district called Dolly. The graveyard was where all the sex that could not take place in Dolly happened. Also, that was where streetwalkers who did not want to be part of the brothel system worked. In the ground was a layer of dead Dutch fighters from a series of wars and occupations in and out of Indonesia, and a few limestone statues. It was segregated from the Chinese graveyard nearby. The limestone for statues was mined from nearby ridges. The gouged cliff faces sparkle white in the sun. People make love against these materials. With flat palms and fingers cresting the edge of the engraved name of the Dutch volcanologist Van Bemmelen. Limestone is not as cold as granite and it is softer. But mostly people hang around and do business by the granite tombs, where the grass is taller and it is easier to be invisible.

The tombs, when you lie on them and look at the sky, begin to look like buildings, like you are on a rooftop. Ruskin loved this, this indistinction between buildings and earth. Cities are reconfigured mountain ranges, he thought. The mountains are mined, crushed, then reassembled into mountain-buildings with bedrooms, verandas, toilets. In quarried holes in the ground we find shadows of buildings. The red-orange brick sandstones of New York walk-ups are the reorganization of upstate subterranean veins. The light-brown clay roof tiles on wooden Javanese buildings are harvested from hills melting into deltas, stamped and fired into a U shape. I remember someone telling me that roof tiles got their U shape by being bent over the thighs of the women who manufactured them. They would sculpt them by hand and their thighs were molds, like riverbanks. I remember looking out the window of a friend’s place onto a ruined old village house on a small island in Hong Kong. A banyan tree was growing through the back room. There was only half a roof left and taro growing off the walls, the plant with massive leaves that look like the faces of elephants. The remaining roof was of thin sheets of flat, fired-clay tiles, stacked so thick that it was a cross section through a hundred million years.

To put the palm on a granite tomb with a finger edging over an inset V while someone behind you touches your collarbone with three fingers and the edge of your pelvic bone where it flares to hold your stomach is ‘to do’ geology. It is to make love to bones at the edge of flesh where it grips to mineral and the inside of the earth.

Over the summer of 2014, Tri Rismaharini, the mayor of Surabaya decided she wanted to close Dolly. She offered the prostitutes compensation of about $500 USD, with which they could find more, she said, “ladylike” work, such as cooking. Some of the sex workers burnt their compensation cards on the street. An underwhelming number of them took the money. On the day the police arrived to evict the brothels they encountered barricades and street fights. In the end the police won. Today, they continue to run daily raids hunting down workers that have dispersed to new alleyways and massage parlors. The graveyard is busier at night with lovers on stone. The cops sweep in, their lights filling the potholes in the dirt road.